GOLDEN, Colorado — It has to be some sort of record. At no time over the five decades of sending robot craft into the heavens have so many spacecraft been on duty at such a variety of far-flung destinations or en route to their targets.

Ballistic buckshot of science gear is now strewn throughout the solar system — and in some cases, like Voyager hardware — have exited our cosmic neighborhood to become an interstellar mission.

But the march of time has also meant that more nations have honed the skills and know-how to explore the solar system. For example, Europe has dispatched probes to the Moon, Mars and Venus — and their Rosetta spacecraft is on a 10-year journey to investigate a comet in 2014.

Meanwhile, Japan's Kaguya and China's Chang'e 1 lunar orbiters have each just settled into an aggressive campaign of surveying the Moon. India is set to orbit the Moon with its Chandrayaan-1 in 2008, and the German space agency is also prepping for a future robotic lunar mission as is the United Kingdom.

All this action at the Moon — including the rekindling of Russian and U.S. lunar missions — bodes well for bolder ventures ever-deeper into the solar system by multiple nations.

And there are other signals stemming from all this outbound traffic.

Opportunity for discovery

"The Moon is a great place that we often take for granted and we feel that we know it well enough. This is a grave mistake," said Stephen Mackwell, Director of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas.

Mackwell explained that we have barely scraped the surface of what the Moon has to tell us. So why then did the Moon take a backseat -- exploration wise -- given that so much remains to be learned?

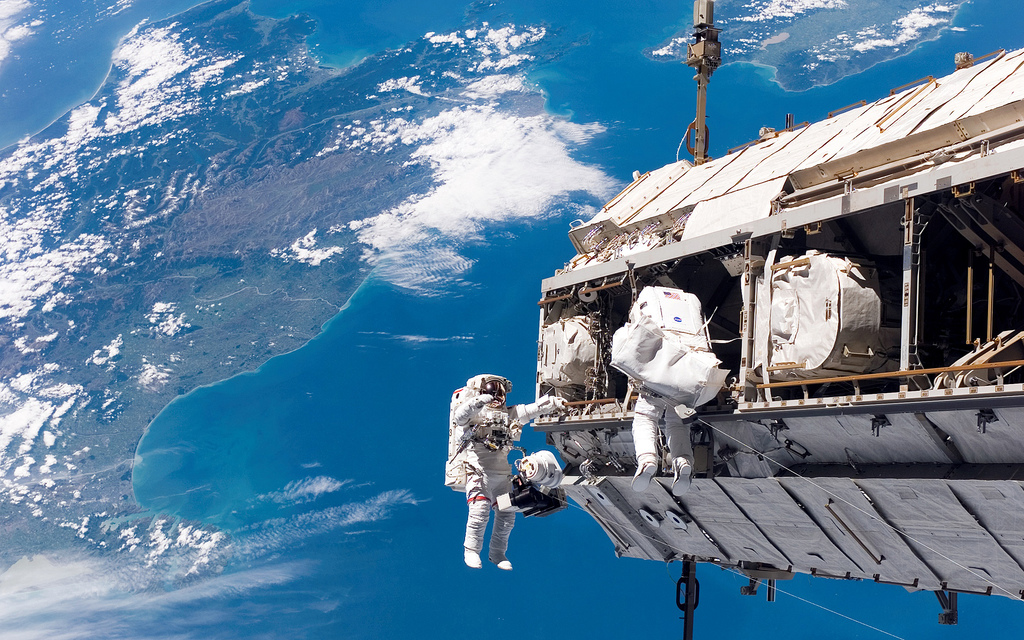

"I guess we became rather addicted to our ability to robotically explore the vast distances of our solar system, and we relegated humans to low Earth orbit and below," Mackwell told SPACE.com. "Mars came to ascendancy as the possible source of living organisms, and we had so many new and exotic places to explore. The further we reached and the closer we looked, the more fascinating these foreign bodies seemed, and we gave up on the Moon," he added.

Now, as more and more lunar imagery and data floods in from Kaguya and Chang'e 1, Mackwell sees a captivating place with "so much opportunity for discovery."

Unresolved questions

Mackwell said that the relegation of the Moon to the history books all changed when the U.S. President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, that's the NASA Moon, Mars and beyond to-do list.

"Suddenly, we were thinking of humans beyond low Earth orbit, and how we would reach out real hands rather than robotic to touch those exotic places," Mackwell pointed out. "And you have to start somewhere...so it makes sense to learn to live off [the] planet in a place close by. Somehow this new vision started people thinking of the Moon again as a place to do science."

That thinking has meant resurfacing and dusting off some old unresolved questions about the Moon, Mackwell continued, bringing them to the fore, such as: How well do we have the cratering record calibrated? Was there really a late heavy bombardment and what caused it? How did the Earth-Moon system really form? Does the Moon have a core? Are there resources on the Moon that would enable human exploration...and is there commercial viability down-line? How about hotels on the Moon?

Making a statement

The number of nations shooting for the Moon is a declaration of sorts.

"A lot of this international activity is clearly about making a statement that they can do it too, and that these countries have come of age technologically in the early part of the 21st century. But one cannot help thinking that there is also the underlying urge to explore the unknown, to open new frontiers. Now the South Koreans and the Canadians are moving forward with their own visions, and the Moon is the logical place to go and test a nation's ability to design, build and test instruments and spacecraft," Mackwell senses.

There is abundant important science to be done, Mackwell continued, regardless of whether it is for science sake or as a precursory activity for eventual human exploration and habitation. "Nobody seems to openly admit there is a space race...yet. But there is certainly a lot going on, and it is inevitable that some milestones will ultimately result in more overt competition," he said.

More chances to partner

"We're certainly outnumbered at the Moon," said Alan Stern, Associate Administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. Still, that present-day situation pales given the space agency's peppering of inner and outer worlds with spacecraft.

Reviewing the number of nations doing or planning space science missions, Stern's outlook is positive. "I think it's good. The more countries studying the Earth and global change, the more countries involved in planetary or astrophysics, solar...it's good for space science and for space exploration," he told SPACE.com.

"Sometimes it's cooperative, sometimes it is competitive...but in terms of the science, whether it is cooperative or competitive, it is probably good," Stern said. "We see more and more chances to partner, not just with the Japanese and Europeans, and the individual European space programs, but the Indians...and the Argentineans doing missions with them in Earth orbit to study our globe. I'm not threatened by any of this. I'm very keen on having a lot more partners," he said.

Stern warning

On the more down-to-Earth side of U.S. robotic space missions, however, there's a "Stern warning" concerning cost overruns and tight budgets.

"We need to increase our flight rates. We need to rev up our Earth science program. We need to get more out of the budget that we have," Stern advised, as well as rebalance the ratio of small to large missions. "A lot of the vigor is taken out of the program when you don't have enough small missions to match the large missions...that it is all large missions."

"The pendulum swung a little too far on that. We need to start pushing that back," Stern said, spotlighting small Explorer missions and Discovery-class spacecraft.

Stern said that NASA has been throwing money away on unexpected cost overruns. "I need to change that behavior, because that's the best way to fund more missions."

The problem, Stern said, has been scientists and science teams that try to put too much in the missions, be it science experiments, technologies or techniques. "When you create a psychology that you always pay for the overruns, then people don't have to mind the store very closely. Overruns need to be rare...not routine."

Big picture

But while NASA is rebalancing its robotic exploration agenda, is NASA losing its touch? Is the U.S. space agency likely to fall behind other nations in space?

"I don't think so," responded Mackwell of the Lunar and Planetary Institute. "We have a vibrant robotic space program with numerous mission opportunities ahead of us. In some ways NASA has done a lot of the easy stuff, and future missions are likely to be more challenging -- and expensive -- as the questions get tougher and more complex," he suggested.

In looking at the big picture, Mackwell pointed out that there are a scad of missions still at Mars, a very healthy Cassini spacecraft doing wonderful science at Saturn, spacecraft are on their respective ways to Mercury and Pluto, and missions under preparation for the Moon, Mars and Jupiter.

"Compared to the number of active NASA missions out there, the number of spacecraft by other nations is more modest," Mackwell said. "Projections for future launches of planetary missions from other nations do not suggest that the rest of the world will overtake NASA in the near future."

So the prognosis for NASA advancing forward in this arena is good, Mackwell said, but not without issues to deal with.

In Mackwell's estimation, the challenges for NASA science include issues with Congress passing a reasonable budget for the space agency that will support both the human and robotic activities; potential taxation of the science budget to pay for shortfalls in human spaceflight and development of the Ares booster; questions about the space policy of a new President; and the escalation of robotic mission costs for both new missions and extended mission activities.

"Nonetheless, the new management of NASA's Science Mission Directorate has a vision and a will to have a healthy mission suite to diverse targets, and strong research and analysis lines to capitalize on the wealth of wondrous new data generated by these missions," Mackwell concluded.

Labels: daily